The Refugee Response Plan (RRP) for the Syrian crisis, in 2014, was focusing mainly on life-saving assistance. From 2015, the now-called 3RP (Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan) includes a resilience component in parallel to the refugee component. This new component aims to move the response to the Syrian refugee crisis from a provision of humanitarian assistance solely to a support of long term self-reliance among the refugee and host communities equally. Building resilience will reduce people’s external dependency and result in a better ability of communities and institutions to absorb future shocks.

The case for a resilience-based development response

UNDP-Iraq has endorsed this approach by launching a research project for “Resilience-building in Syrian refugee camps and their neighbouring host communities in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq”, which has been implemented by the Middle East Research Institute (MERI). Internal and external factors to the crisis in Iraq are reinforcing the push to a more development-oriented response: (i) diminishing aid funds from the international community; (ii) protracted stay of the refugees in Iraq and Kurdistan; and (iii) lack of a solid financial basis of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) to match the humanitarian support that refugees are receiving currently from the international community. This latter point is important, as it implies that the KRG cannot substitute for the humanitarian partners but capacity-building for KRG’s service delivery mechanisms needs to be taken forward.

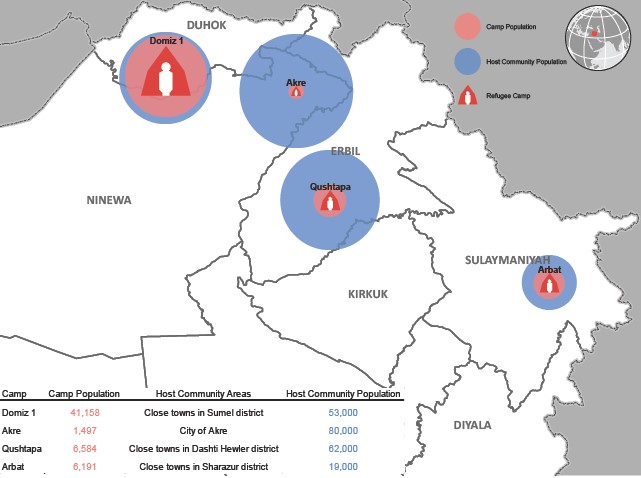

The particular scope adopted within this study consists on promoting resilience in the refugee camps but, as well, in their immediate neighbouring towns and villages, as the evolution of the refugee community is linked to the dynamics within the host community. The camps assessed were Domiz, Akre, Qushtapa and Arbat, as these camps were seen with the necessary characteristics that would facilitate resilience-building. The total refugee population in these camps is 62,650 individuals, while the local population living immediately around the camps was estimated to be at around 214,000 individuals, based on district population figures.

How far is the situation to be resilient?

In the development context, the implication for resilience is that the overall system is able to meet and sustain acceptable social, economic and environmental conditions without humanitarian relief. Hence, this approach combines two dimensions: human resilience is based on people’s capacity to sustain their livelihoods, and institutional resilience is based on the capacity of the national system to meet and maintain the delivery of public goods and services.

Both dimensions of resilience were evaluated within the study in order to create a livelihood baseline and identify key resilience-building requirements for both in-camp Syrian refugees and the neighbouring communities.

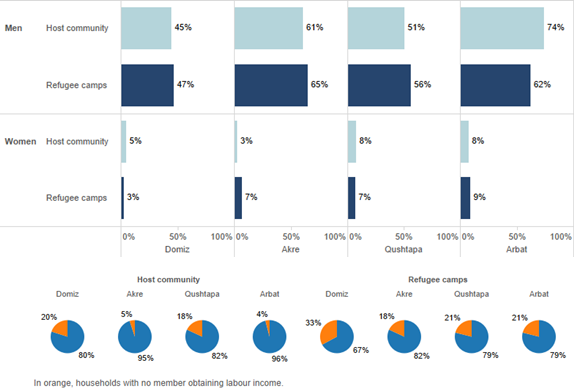

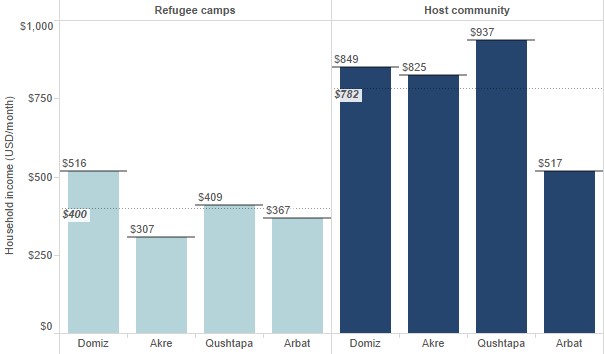

In terms of human resilience, in spite of the economic slowdown, rates of participation in the labour force are very similar between refugees and host community. 32% of the population between the age of 16 and 59 are employed (see Figure 1). A policy of free movement in and out of the camp and the facilitation of work permits allows refugee to freely pursue employment opportunities. However, the employment situation, in terms of type and quality of jobs, severely undermines refugees’ livelihoods. Due to the functioning of the regional labour market, refugees mostly work in unskilled positions, irrespective of their qualifications, and the work available is frequently temporal. There is also a higher proportion of refugee households with no income from labour. As a general result, the average household income is largely lower for refugees if compared to the host community (see Figure 2).

In addition, there has been a successful focus on supporting business entrepreneurship within the camps, but it must be taken into account that still the camp setting is a very closed economy, with a very limited market. There is a big risk to fall into an excess of internal competition and non-profitable (hence, non-sustainable) businesses in the camps if barriers are not addressed. A crucial barrier, for instance, is the legal constraint of refugees to initiate a business outside of the camp because property rights are not recognised.

Figure 1. Employment rates among adult population and households with no labour income

Regarding institutional resilience, the provision of public services in Kurdistan was subjected to severe capacity constraints before the onset of the crisis in many areas, such as education, health or municipal services. Hence, these are even more constrained nowadays due to a combination of inability to sustain the funding and a large shock in the demand-side. The public service provision in the camps is a mix of services managed by the governorates and services managed by the humanitarian partners. The level of services is similar, or even higher, to the host community, except in water provision where large investments are still required. Hence, building institutional resilience does not imply that all responsibility has to be gradually left in the hands of the local authorities, which do not have the necessary capacity, but the international support has to be continuous and more targeted to capacity building for Kurdistan’s institutions. Above all, however, institutional resilience will not be solved at camp-level. It depends inevitably on a system-wide resilience still to be achieved.

Figure 2. Comparison of household monthly income between host community and refugees

Key principles to take forward

Taking into consideration the differences between the refugee and host communities in terms of livelihoods, resilience targets were established that would grant in-camp refugees similar living standards as the host community. In addition, enhanced targets were agreed so that they form a buffer in which households can rely without falling beyond the minimum living standards in case of shock.

The main conclusion of the study is that it is feasible to bring the standards of both communities up to the resilient targets proposed, but only through a combination of two types of intervention. First, livelihoods support targeted to refugees and host community must be boosted, such as building credit and saving facilities, improving the value chain in which they participate, supporting employment allocation schemes, encouraging women participation in the labour market and exploring new areas like agro-processing —not forgetting targeted institutional building to strengthen basic infrastructure and service delivery mechanisms to ensure access to quality services at affordable cost both in normal times and in situations of stress. Second, advocacy for key policy changes is required, such as labour market reforms, better protection of employment rights, legal property rights of refugees and participation in safety nets, that would contribute to better and more diverse employment opportunities —and bridge the household income gap.

During the roundtable with stakeholders organised as part of this study, the KRG Ministry of Planning endorsed the same resilience-based approach that the humanitarian community is promoting. Some clear messages came that can put all relevant actors rowing on the same direction, starting from forming a steering committee for resilience, continuing with a better use of local dissemination channels, and ending by creating a trust fund to initiate the transition towards a resilience-based development response on which everybody agrees.

An edited version of this article has been published in the internal magazine of July 2015 of UNHCR’s Syria Regional Refugee Response, downloadable here.

* * * * *

About MERI: The Middle East Research Institute is Iraq’s leading policy-research institute and think tank. It is an independent, entirely grant-funded not-for-profit organisation, based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region. Its mission is to contribute to the process of nation-building, state-building and democratisation via engagement, research, analysis and policy debates.

MERI’s main objectives include promoting and developing human rights, good governance, the rule of law and social and economic prosperity. MERI conduct high impact, high quality research (including purpose-based field work) and has published extensively in areas of: human rights, government reform, international politics, national security, ISIS, refugees, IDPs, minority rights (Christians, Yezidis, Turkmen, Shabaks, Sabi mandeans), Baghdad-Erbil relations, Hashd Al-Shabi, Peshmarga, violence against women, civil society. MERI engages policy- and decision-makers, the civil society and general public via publication, focused group discussions and conferences (MERI Forum).